On July 13th, 2019, Zarious Malikai Fair was walking to his cousin’s house in the East Bluff. The 16-year-old had just received his first paycheck ever from working at Jonah’s Seafood House in East Peoria. He worked as a busboy alongside his father, Demarco Fair, who worked as a cook. Zarious liked playing the video game Fortnight, drawing anime, riding his bike, playing basketball, and collecting Nike Airforce 1’s and Jordans. “He was going to school. He had a job. He wanted to get out of Peoria because he wanted to make something of him and of his life,” his mother, Gamiake Makori said.1

But, as Zarious made his way down Frye street towards his cousin’s house, he was stopped by two teenagers with intentions to rob the boy of anything they found. According to a witness report, Doyle E. Nelson Jr., 18, allegedly ordered Zarious to give them anything he had. Zarious said he had no money on him, only a check made out to him from his job. Doyle proceeded to pat the boy down to verify. It was then that Zaveon Marks, 14, allegedly pulled out a gun and shot Zarious three times in the torso. Zarious died 20 minutes later of blood loss. He became Peoria’s 11th homicide victim for 2019. Rest in Power – 2003-2019. (Attempts were made to get a comment from Zarious Fair’s family but were not responded too.)

Both Doyle Nelson and Zaveon Marks were arrested shortly afterward. Despite not pulling the trigger, prosecutors allege Doyle’s involvement in the attempted armed robbery makes him culpable in the murder.

Zaveon was initially charged in juvenile court with two counts of first-degree murder and one count of unlawful possession of a fire arm. This was quickly followed by the same charges being filed in adult court and an ensuing tug-o-war between the juvenile and adult courts on whether the 14 year old is legally culpable of the murder as an adult or not. If the boy had been at least 16 years of age, the question of him being tried as an adult wouldn’t have been brought up at court, as Illinois has a statutory requirement to automatically prosecute 16-17 year olds as adults for “(i) first degree murder, (ii) aggravated criminal sexual assault, or (iii) aggravated battery with a firearm . . . where the [youth] personally discharged a firearm.”2 “But kids ages 13 to 15 can also be tried as adults under a discretionary transfer, if a judge decides it’s in the public’s best interest.”3 After being moved from juvenile court to adult court in mid-August, the teen was moved back to juvenile court in September. This was mainly due to technicality issues and the prosecution’s desire to fend off any appellate challenges years later if the boy is convicted. However, Judge Frank Ierulli of the juvenile court reaffirmed his earlier decision to send Zaveon to the adult division. Ierulli said “that he found no reason to keep Zaveon Mark’s case within the juvenile system, and that he didn’t think the boy was a ‘naive young man.’”4 Furthermore, Judge Ierulli said, “This kid is street smart and savvy, he knows what to do and when to do it.”5 The judge even went so far as to recognize the boy’s poise with the implication seeming to be he acted more mature than the average 14-year old child.

The consequences of this decision–to Adult or Not to Adult–is no trivial matter. Possible sentencing if convicted varies drastically between the two. On the one hand, if convicted as a juvenile, he could be sentenced to an indeterminate amount of time in detention with the focus on rehabilitation but would be released from Juvenile Detention Center (JDC) when he ages out of the juvenile system at 21. On the other hand, conviction as an adult could leave Zaveon in prison practically for the rest of his life. Adults convicted of murder are typically sentenced between 20-60 years in prison. Illinois statute requires convicted murderers to serve 100 percent of their sentence before release. If the murder was committed using the discharge of a fire arm, a mandatory consecutive 45-year sentence is tacked on. Because Zaveon is a minor, the rules for charging him are a little different. He could still face anywhere from 20-60 years. However, in order to sentence the boy to 41-60 years, the court would have to determine the 14-year-old is particularly depraved and beyond the possibility of rehabilitation, which is a very high barrier to meet. Zaveon would be imprisoned at JDC until he turns 21, then transferred to an adult prison to serve the remainder of his sentence. According to local attorney Susan O’Neil, “They rarely keep juveniles until their 21st birthday, even if the judge in JD court sentences them to a ‘full commitment.’”

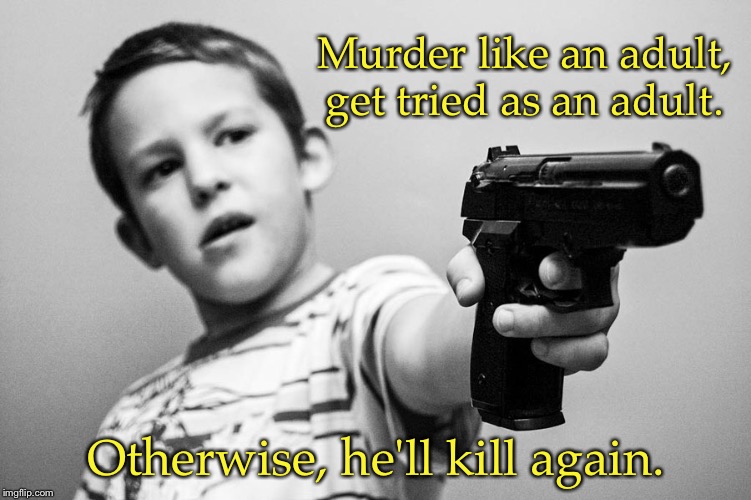

The decision of whether to try the 14-year old Zaveon Marks as an adult or not has created no small difference of opinions. On one side of the debate, are those Peorians who fervently believe in the ideology of “tough-on-crime”. In order to seek revenge against law-breakers and deter other criminals from engaging in the same illicit acts, society must incapacitate criminals with maximum pain and time.6 Any relevance about Zaveon’s young age is mitigated by the seriousness of the crime. “He committed the most serious adult crime there is so he should face adult punishment.” “He picked up a gun like a man, so he should be punished like a man.” “We have to punish him as harshly as possible to prevent others from doing the same thing.” “If you take a life, you forfeit your own life.” “He’s old enough to know murder is wrong.” These are the general sentiments amongst the tough-on-crime crowd.

And there’s good reason to assume this is the most popular way of playing, not just in Peoria, but in the nation at large. Since the 1970s, tougher, longer, and more onerous sentences–with the focus not on rehabilitation but on incapacitation–have been the status-quo in the U.S. leading to the largest prison population on the planet. As Chief Justice Roberts stated in his dissenting opinion on whether to punish juveniles with life without parole, “it is not unusual” for minors to be sentenced to life in prison.7 There are currently 2,100 individuals facing life without the possibility for parole because of crimes committed as a juvenile.8 29 states, including Illinois, have no prohibition against sentencing juveniles to life without the possibility of parole.9 An informal poll posted on the Peoria-area Facebook group Daily Commitment Report showed 65 percent of people believed the boy should be tried as an adult (this includes Facebook user Gamiake Makori, mother of Zarious Fair).

Proponents of tough-on-crime for 14-year-old Zaveon point to the fact the child was already on probation for an armed robbery he had committed earlier this year as the failure of the juvenile court system to rehabilitate the boy. And, it’s hard to argue with the idea the juvenile court system failed to address this very serious concern. Zaveon did (allegedly) escalate his violence from armed robbery to murder. These facts seem to rule out the possibility of rehabilitation in general for this boy.

But there is also a side of the debate that disagrees with the propositions of the tough-on-crime crowd:

“The United States made a thoughtful and deliberate choice in 1899 to accommodate developmental differences between adolescents and adults with the establishment of juvenile courts. The reforms of that era created a separate system of justice for juveniles that recognized differences in culpability and maturity.”10

This is not to say they believe murders committed by minors should go unpunished. Nor do they believe the death of Zarious Fair wasn’t a terrible tragedy. Those of us who urge caution in trying Zaveon as an adult, do so recognizing the incomprehensible passions that involve the brutal murder of someone’s child. This intense desire of revenge stems from a desire to feel closure regarding the absence of a loved one. This absence is ultimately unsurpassable in the sense that its lack, i.e., the positive existence of the victim, is forever out of reach. Murder is that serious. It can never be taken back once someone has achieved the impossible possibility of not-living. It is for these reasons humanity has generally recognized murder as arguably one of most serious offenses against both an individual and society.11

There’s little doubt that even young children know murdering someone is wrong, let alone a 14-year-old boy. But the question isn’t whether he knew it was wrong or not, but whether his culpability is the equivalent of an adult. The brain of a juvenile (roughly ages 10-25) is fundamentally different from both children and adults, “especially in the areas involved with behavior control, planning, and risk avoidance.”12 There are several reasons for this. Different areas of the brain mature at different rates. During adolescence, the area of the brain that regulates fear (the amygdala) and the reward center of the brain (the insular cortex) are incredibly precocious, developing much faster than the pre-frontal cortex where reasoning and executive control functions happen. Adolescents experience, on average, greater fear and anxiety than both children and adults. “This means that adolescents have a brain that is wired with an enhanced capacity for fear and anxiety, but is relatively underdeveloped when it comes to calm reasoning.”13 This is one of the primary reasons it is so difficult for adolescents to control their emotions. This is only compounded if the individual has mental health issues like bipolar disorder. “In emotionally charged situations, this less developed circuitry appears even less capable of adequately regulating emotions and actions, resulting in a teen exercising less self-control in making a risky decision, even when he or she knows better.”14

Another important factor to consider is the effect of peer pressure on adolescents. In the aptly titled “Friends Can Be Dangerous,” professor of psychology Laurence Steinberg points to an experiment where subjects were asked to play a driving video game. Some were observed playing the game alone, while others were observed playing the game with peers. “The mere presence of peers made teenagers take more risks and crash more often, but no such effect was observed among adults.”15 Statistics from the FBI show that juveniles commit more crime in groups than do adults. Even driving statistics show that there is an increase in crashes among teenagers with same-age passengers, while no such effect exists with adults.16 Steinberg’s research illuminates how peer pressure is not limited to explicit encouragement of illicit activities, but the mere presence of peers increases the likelihood of risky behavior. When around other teens, the reward center of the brain is often hyperactive. “This inclined teenagers to pay more attention to the possible benefits of a risky choice than to the likely costs, and to make risky decisions rather than play it safe.”17 Furthermore, evidence suggests that criminal behavior tends to be present oriented,18 and Steinberg’s research shows that the presence of peers draws teenagers “to immediate, rather than longer-term, rewards.”19

There’s another important factor that I would be remiss not to bring into relief: race. Zaveon, his accomplice, and their victim, Zarious, were all African-Americans. When it comes to charging juveniles as adults the data shows a disproportionate amount of black juveniles are tried as adults compared to white juveniles who commit the same offense. Laura Cohen, the director of the Criminal and Youth Justice Clinic at Rutgers Law School, says:

Prosecutors just don’t ask to try white kids as adults at the same rates. Controlling for nature of offense, controlling for family background, controlling for educational history — all of the things that go into a prosecutor’s decision, there are still disparities, significant disparities, that cannot be explained by anything other than race.”20

In Illinois, more black children are charged as adults than white children, despite making up a fraction of the youth population.21 There’s a plethora of research that may explain why this phenomena is so common. In most societies, children are categorized in a distinct group possessing qualities of innocence along with an inherent need to protect. However, research shows that black children are often viewed by police, the criminal justice system, and society at-large as older, more aggressive, and more culpable for their actions. “Our research found that black boys can be seen as responsible for their actions at an age when white boys still benefit from the assumption that children are essentially innocent,” said author Phillip Atiba Goff, PhD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.22 Further studies show that “white people apparently have a “superhumanization bias” when it comes to black people— that is, they associate them with superhuman abilities,” like super-strength or an inability to feel pain.23 Even black-sounding names (DeShawn or Jamal) seem to trigger an unconscious idea that these individuals are more prone to violence than white-sounding names (Adam or Michael). “I’ve never been so disgusted by my own data,” Colin Holbrook, the lead author of the study said, “The amount that our study participants assumed based only on a name was remarkable. A character with a black-sounding name was assumed to be physically larger, more prone to aggression, and lower in status than a character with a white-sounding name.”24

It’s important to remember that racial bias is not limited to explicit racists sentiments, but include often unconscious yet split-second biases. With the research we’ve seen, it’s at least worth asking if their was any racial bias in Judge Ierulli’s above statement that a 14-year old Zaveon had the poise and savvy street smarts of an adult. Especially considering that no matter how mature the boy looks, the science is clear that his brain is not developed to the same level as an adult.25

Furthermore, we know there are other racial disparities in criminal justice system in Peoria. “Peoria County is second only to Cook County in the number of juveniles in the criminal justice system from all of 2018 through the first quarter of 2019, based on information from the Illinois State Police.”26 With two-thirds of juvenile prisoners being black, it is safe to assume most of the youth entering the criminal justice system are youth of color. “68.5% of all people sentenced to prison from Peoria County were Black, even though African Americans are only 19% of Peoria County.”27 In federal court, prosecutors can impose sentence enhancements requiring judges to double mandatory sentences:

The Central District of Illinois, including Peoria, Springfield, Rock Island and Urbana, is highest in the nation for enhanced charges against nonviolent drug offenders, according to a report by the U.S. Sentencing Commission. In the Central District, 74.6 percent of eligible cases receive enhanced charges compared with 12.3 percent nationwide… The most recent report by the U.S. Sentencing Commission found enhancements most significantly impacted African Americans. The report states Black offenders comprised 42.2 percent of cases eligible for enhanced sentencing but 51.2 percent of the cases in which enhancements were imposed.28

If the argument here is Zaveon should be tried in the juvenile system, then it is worth analyzing the efficacy of the Illinois Juvenile system. Zaveon was already a part of the system, having been convicted in March for an armed robbery he committed back in January of 2019. He was sentenced to home detention from March till May, followed by probation, which he was still on when he allegedly murdered Zarious Fair. Clearly this was not enough of an intervention to rehabilitate the boy.

There are currently a little over 12,000 juveniles being held by the Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice (IDJJ). Juvenile detention centers typically offer a greater range of services than adult jails and prisons because the focus is ostensibly on rehabilitation. Yet, a report card on the efficacy of IDJJ would likely be graded very poorly. Recidivism rates among juveniles in Illinois are very high.

- 87 percent of youth released from IDJJ are rearrested within a 3-year period.

- 64 percent of those rearrested are African American, and 93 percent are male.

- 90 percent of black youth released are rearrested within 3 years, compared to 87 percent for Latinx youth, and 79 percent for white youths.

- 55 percent of youth released from IDJJ are recommitted to detention with a 3-year period.

- 65 percent are black, followed by 25 percent of white youth, and 10 percent. of Latinx youth.

With a report card like this, it is easy to see why the tough-on-crime crowd is so skeptical of the juvenile system, especially with regards to Zaveon Marks. We might even be convinced to continually call for longer and more draconian penalties for both juveniles and adults. However, there is a growing consensus among criminology experts that lengthy sentences for crime do little to deter criminals. Many studies “suggest that increases in the severity of punishment have at best only a modest deterrent effect.”29 In fact, perpetrators sentenced to prison often have higher recidivism rates than those sentenced with alternative sanctions.30 States like Illinois, with particularly harsh sentences for gun crimes,31 have not seen a reduction in gun crimes.32 As described above, offenders tend to be very present-oriented (especially juveniles), therefore lengthier sentences are unlikely to actually deter future crimes any more than shorter sentences. Since Zaveon could be sentenced with as much as 60 years in prison (a virtual life sentence), it’s worth looking at the inadequacies of the death penalty in deterring crime (life sentences are often considered the “other” death penalty). It is generally recognized that the death penalty is insufficient for actually deterring crime. Those that commit unlawful murder often fall into one of three categories: crime of passion, psychopathy, or are part of a criminal syndicate. With “crimes of passion” the perpetrator is not in the correct mindset to fully appreciate the long-term consequences of their actions (though this does not absolve them of culpability). Both psychopathy and criminal syndicates are largely indifferent to the moral and legal consequences of murder. Therefore, such harsh penalties are highly unlikely to deter future crime.

So, what is the answer to dealing with juveniles who commit serious crimes? There are examples to be analyzed where the Juvenile system is far more successful at rehabilitating offenders and sports a significantly lower recidivism rate than Illinois. For instance, Germany boasts a recidivism rate of 30 percent among juveniles and young adults, a pittance compared to Illinois’ 86 percent.33 German officials recognize the emotional and mental limitations that should preclude juveniles from adult consequences. In Germany, anyone under 21 is treated like a juvenile and sent to the juvenile court systems:

In Germany, prisons are supposed to mirror the outside world. Officials say that helps prisoners learn how to live a life without crime when they get out. Every prisoner has a job that pays minimum wage. And there are coffee pots all over the prison where inmates gather with glass mugs and metal teaspoons.” German officials say, “young inmates need a lot of coffee — they’re not used to working a full day.“34

Beyond this, society must address other issues that generally lead to crime, especially within the minority community. The only way to do this is to analyze the backgrounds of juvenile perpetrators. Let’s look at the example of Zaveon. Zaveon was raised in the West Side of Rockford and spent a short time in Peoria’s East Bluff neighborhood, both well-known for having high crime rates. Both his father and step-father are currently incarcerated.35 Zaveon’s mother has always been in his life and has no criminal record. Zaveon’s father, Rashund Marks, has a long criminal history involving multiple convictions for all types of illegal drugs. He is currently serving a federal sentence for 2011 convictions of possession of a weapon and delivery of drugs.

Zaveon’s mother later married a man named Halbert “Angel” Taylor. Zaveon’s defense attorney, William Loeffel, described the marriage as rife with domestic abuse. There were multiple orders of protection between the mother and Taylor, eventually leading to Taylor’s conviction and imprisonment for aggravated domestic battery. This history of violence is certainly no excuse for the horrendous crimes Zaveon is accused of. Most survivors of domestic and childhood violence do not become murderers. But it helps us see what led a 14-year-old brain to believe violence was the best answer to this specific, tragic incident. “Violence is a learned behavior, and when it is demonstrated by adults in a home environment as a tool to resolve problems, children internalize this and, without intervention, are prone to repeat it.”36

Zaveon has an IQ of 70-85 according to his attorney who said it was on the low end. Despite this, the boy was never in any special education classes or covered by an IEP. He had a typical disciplinary record at school, but there were no expulsions. Zaveon would have attended Peoria Heights High School as a Freshmen had he not been arrested. His attorney said the boy has no history of mental health concerns, and the attorney has no plans to call for a fitness exam in court. However, it is worth looking at the effects of violence on the brain, if for nothing else, but to try to prevent another senseless murder. New research over the last decade has revealed that many people who live and grow up in high crime areas have untreated forms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). “We found that traumatic experience and PTSD associated with being aggressive across sexes of an inner city population.”37 The trauma that one can experience living in the East Bluff of Peoria or the West Side of Rockford can be caused by direct forms of violence like assaults or domestic abuse; but it can also include acts of violence that are not specifically directed at the traumatized individual like consistently hearing gun shots in your neighborhood or witnessing domestic violence between parents or loved ones. If this trauma goes untreated it can lead to several deleterious effects: lower empathic resonance, deficits in mentalizing and emotion recognition, lower levels of empathic concern, decreased perspective taking and difficulty recognizing social relationships.38 It’s not a stretch to see these symptoms manifest among gang members and other inner city criminals. Left untreated, PTSD can develop into very self-destructive survival strategies. Zaveon was raised in violent neighborhoods and witnessed domestic violence in his own family. Again, this is not to excuse dangerous behavior that harms society. Most people who witness violence in their neighborhoods and homes do not go on to commit murder.

Finally, there’s final consideration that must be accounted for and is often completely absent from criminological analyses: lead. The same lead which has poisioned Flint, Michigan for almost six years can still be found commonly in older houses. Any house built before the 80s, there’s a good chance lead is in the paint if not also in the water. The East Bluff, Near North Side, and South Side are littered with 100 year old houses riddled with lead (I had the unfortunate displeasure of living in such a house in the East Bluff).

Lead has been known for centuries to lead to lower IQs, increased aggression and criminality. “The lead-crime hypothesis is pretty simple: lead poisoning degrades the development of childhood brains in ways that increase aggression, reduce impulse control, and impair the executive functions that allow people to understand the consequences of their actions. Because of this, infants who are exposed to high levels of lead are more likely to commit violent crimes later in life.”39 The effect lead has had on the human species cannot be underestimated. “The effect of childhood lead poisoning is permanent loss of tissue in the anterior cingular cortex (ACC), which controls emotional regulation, impulse control, attention, verbal reasoning, and mental flexibility.”40

In the 20th century, almost every country that increased their use of lead in petroleum, paint, and other goods saw a corresponding rise in violent crimes during this period. Towards the end of the century, as countries began to ban lead from gasoline & paint, there was a corresponding decrease in crime. “Since 1991, violent crime rates have declined across the board. However, the arrest rate for black juveniles has dropped more sharply than the rate for white juveniles. Why? Because blacks were more affected by lead in the 60s and 70s. Their crime rate went up more than it did for whites, so when lead was removed from gasoline their crime rate went down more than it did for whites.”41

Though lead does not explain all crime and there are many different factors effecting crime, lead is underestimated in its influence. The most crime ridden neighborhoods in Peoria are correspondingly home to most of the older homes many of which have lead in the paint and pipes.

If it was up to me, Zaveon Marks would be tried as a juvenile and sent to JDC for rehabilitation. However, it is hard to justify the sentence he would receive under this scheme. A seven-year stint in JDC would certainly not be justice for Zarious Fair or his family. They deserve more without question. At the very least, the sentencing statutes for minors who commit murder should be changed. I would recommend a minimum fifteen-year sentence in JDC for juveniles who kill others. Follow the model in Europe, require the boy to get a job, get educated, and pay significant restitution to the family of Zarious Fair. I do not believe sentencing Zaveon to 40 or more years in prison will prevent the next murder of a minor or murder by a minor in Peoria. The inner city of Peoria desperately needs more resources and they won’t receive those if society is spending millions of dollars imprisoning its residents. The total cost for a 40-50 year sentence for Zaveon could reach as high as 2.5 million dollars.42

I reached out to both the NAACP of Peoria and the Black Justice Project for their opinion’s on trying Zaveon as an adult. Both organizations declined to comment. However, local activist & president of the local ACLU, Spanky Edwards, had this to say, “My personal opinion is wtf is there juvenile court for if kids can be charged as an adult? The brothers race and class has to do with that.”

Zaveon will be in court October 28th for his jury trial. It is unlikely any other 14-year-olds will be on the jury, which strains the credulity of him being tried by a jury of his peers. Zaveon Marks is innocent until proven guilty.

UPDATE 10/31/2020: 14-year old Zaveon Marks was found guilty by a jury in Peoria County for the murder of 16-year old Zarious Fair. Predictably, there were no other 14-year olds on this jury of his peers. In July, both Marks and 18-year old Doyle E. Nelson were arrested for the murder. Zarious Fair was Peoria’s 11th homicide of 2019.

“During the three-day trial, prosecutors hammered home that Marks and another man, Doyle Nelson, 18, came up behind Fair and another girl as they were walking in the 700 block of East Frye Avenue shortly after 4 p.m. The girl testified that Marks indicated he wanted to rob Fair, though she told jurors that it appeared the two boys would start fighting. Nelson rooted through Fair’s pockets, finding nothing. Then, the girl said, Marks fired four times, striking Fair three times.” 43

Photo courtesy of Andy Kravetz @ Peoria Journal Star

Zaveon’s defense team, Yolanda Riley & William Loeffel, argued Marks was under the influence of the older and more wordly Nelson (whose trial will not begin until November 18th). The defense said Nelson was a bad influence and had a habit of hanging out with young boys urging them to carry weapons. A 15-year old girl who testified against Marks stated the shooter was wearing a black hoodie. However, it was Nelson who wore a black hoodie that day. The defense team used this to say Nelson was the actual shooter, not Zaveon.

Zaveon is the youngest person convicted of murder in over 20 years.

UPDATE 10/18/2020: Over a year later, a 15-year old Zaveon Marks was finally sentenced for the 2019 murder of 16-year old Zarious Fair. Zaveon was charged as an adult.

Circuit Court Judge Katherine Gorman made the legal finding that the 15-year old was particularly depraved and beyond the possibility of rehabilitation. She sentenced Zaveon to 45 years in prison. This legal opinion is necessary in order to charge the minor with anything over 40 years. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that life sentences for juveniles violated the 8th Amendment; and, the Illinois Supreme Court has found anything over 40 years is considered a life sentence and would not include juveniles except in cases where a legal finding is made that the juvenile is beyond the possibility of rehabilitation.

Zaveon will be imprisoned at JDC until he turns 21, and then transferred to an adult prison to serve the remainder of his sentence. According to local attorney Susan O’Neil, “They rarely keep juveniles until their 21st birthday, even if the judge in JD court sentences them to a ‘full commitment.”

Circuit Judge Katherine Gorman said the shooting was senseless and unnecessary. She told Marks the community needed to feel safe from being shot by juveniles carrying handguns.44

“I hope you prove me wrong, Mr. Marks, and that you take advantage of the opportunities that you will have while in custody,” Judge Gorman said.

Exactly how this draconian sentence will make the community safer is difficult to determine. All the evidence I’ve listed above shows this harsh sentence is highly unlikely to deter the next troubled teen from committing a heinous act. This sentence will likely cost taxpayers nearly $2.5 million to incapacitate Zaveon; money that is very much needed in the neighborhoods Zaveon comes from. Contrary to Gorman’s legal finding, the evidence shows “these individuals have a substantial capacity for rehabilitation, but many states deny this opportunity: approximately 62% of people sentenced to life without parole as juveniles reported not participating in prison programs in large part due to state prison policies that prohibit their participation or limited program availability. They typically receive fewer rehabilitative services than other prisoners.”45

Zaveon Marks will be eligible for parole after 20 years, when he will be about 35. If required to serve his full sentence, he’ll be nearly 60 before he exits prison.

UPDATED: 10/26/2019; 10/31/2020

This article was originally published on Strangecornersofthought.com.

- Kravetz, Andy, and Chris Kaergard. “Family: First Paycheck Led to Illinois Teen’s Shooting Death in Attempted Robbery.” Peoria Journal Star, 14 June 2019.

- http://www.ilga.gov/legislation/ilcs/fulltext.asp?DocName=070504050K5-130

- Vollmer, Dana. “Murder Charges In Death Of Peoria Teen Raise Questions About Controversial State Laws.” Peoria Public Radio, 23 Aug. 2019.

- Kravetz, Andy. “Murder Case of 14-Year-Old Moved Back to Adult Court.” Journal Star, Journal Star, 21 Sept. 2019.

- Cannon, Sherry. “The Struggle Continues…. The Good Ole Boys By Sherry Cannon.” The Traveler Weekly, 22 Sept. 2019.

- Tough-on-crime includes the Broken Windows Theory of fighting crime, which I’ve written about here.

- For this reason, Roberts claimed the 8th amendment ban on “cruel and unusual punishment” did not apply precisely because the practice of imprisoning juvenile murderers with life is so common. See Miller v Alabama Supreme Court Decision https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/11pdf/10-9646g2i8.pdf

- Rovner, Josh. “Juvenile Life Without Parole: An Overview.” The Sentencing Project, 23 July 2019.

- Ibid.

- Nellis, Ashley. The Lives of Juvenile Lifers: Findings from a National Survey. The Sentencing Project, 2012.

- However, all of humanity has consistently had an endless list of exclusions to prohibitions of murder.

- Gertner, Nancy. “Locking up Kids for Life? – The Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com, The Boston Globe, 19 Jan. 2014.

- Friedman, Richard. “Why Teenagers Act Crazy.” The New York Times, 19 Jan. 2014.

- Emphasis added. Cohen, Alexandra Ochoa & Casey, B.J.. (2014). Rewiring juvenile justice: The intersection of developmental neuroscience and legal policy. Trends in cognitive sciences. 18. 63-65. 10.1016/j.tics.2013.11.002.

- Steinberg, Laurence. “Friends Can Be Dangerous.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 25 Apr. 2014.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Marie Gottschalk, “No Way Out? Life Sentences and the Politics of Penal Reform,” in Charles Ogletree and Austin Sarat, eds., Life Without Parole: America’s New Death Penalty (New York: NYU Press, forthcoming).

- Steinberg, “Friends Can Be Dangerous.”

- Gonzalez, Sarah. “Kids in Prison: Getting Tried as An Adult Depends on Skin Color: WNYC: New York Public Radio, Podcasts, Live Streaming Radio, News.” WNYC, WNYC: New York Public Radio, 10 Oct. 2016.

- “Trial and Sentencing of Youth as Adults in the Illinois Justice System: 2018 Transfer Data Report.” Juvenile Transfers CY2016 Report_FINAL, Illinois Juvenile Justice Commission, Feb. 2018.

- Goff, Phillip Atiba. “Black Boys Viewed as Older, Less Innocent Than Whites, Research Finds.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 6 Mar. 2014.

- Waytz, Adam, et al. “A Superhumanization Bias in Whites’ Perceptions of Blacks.” Social Psychological and Personality Science, vol. 6, no. 3, 1 Apr. 2015, pp. 352–359.

- Hewitt, Alison. “A ‘Black’-Sounding Name Makes People Imagine a Larger, More Dangerous Person, UCLA Study Shows.” Newsroom, UCLA, 7 Oct. 2015.

- This logic is strikingly familiar to those who abuse teenage girls saying they act more “mature” than their age. Would Judge Ierulli accept a similar argument from a man facing charges of statutory rape?

- Cannon, “The Struggle Continues… Good Ole Boys”

- Ibid.

- Howard, Clare. “No. 1 in Nation for ‘Draconian,” Mandatory Drug Sentencing.” The Community Word, The Community Word, 25 Apr. 2019.

- Steven N. Durlauf and Daniel S. Nagin, “Imprisonment and Crime: Can Both Be Reduced?,” Criminology & Public Policy 10.1 (Feb. 2011): 13–54

- Daniel S. Nagin, Francis T. Cullen, and Cheryl Lero Jonson, “Imprisonment and Reoffending,” in Michael Tonry, ed., Crime and Justice: A Review of Research 38 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009): 115–200.

- A murder committed using a gun carries a mandatory minimum 45 year sentence.

- Durlauf and Nagin, “Imprisonment and Crime: Can Both Be Reduced?,” 2011.

- Gonzalez, Sarah. “Kids in Prison: Germany Has a Different Approach, Better Results: WNYC: New York Public Radio, Podcasts, Live Streaming Radio, News.” WNYC, New York Public Radio, 10 Oct. 2016.

- Ibid.

- “Parental incarceration is often associated with emotional and behavioral problems among their children, including elevated aggression, violence, defiance, cognitive and developmental delays, and extreme antisocial behavior. Children of incarcerated parents are also more likely to drop out of school, become delinquent, and subsequently become confined in institutions themselves.” see Nellis,The Lives of Juvenile Lifers: Findings from a National Survey.

- Ibid.

- Gillikin, Cynthia et al. “Trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms associate with violence in inner city civilians.” Journal of psychiatric research vol. 83 (2016): 1-7. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.07.027

- Ibid.

- Drum, Kevin. “An Updated Lead-Crime Roundup for 2018.” Mother Jones, 12 Feb. 2018.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Housing juveniles for a life sentence requires decades of public expenditures. Nationally, it costs $34,135 per year to house an average prisoner. This cost roughly doubles when that prisoner is over 50. Therefore, a 50-year sentence for a 16-year old will cost approximately $2.25 million.” see Josh. “Juvenile Life Without Parole: An Overview.” 2019.

- Kravetz, Andy. “14-Year-Old Boy Found Guilty of Peoria Murder.” Journal Star, Journal Star, 30 Oct. 2019.

- Kravetz, Andy. “Peoria teen sentenced to 45 years for murder.” Journal Star, Journal Star, 13 Oct. 2020.

- Josh. “Juvenile Life Without Parole: An Overview.” 2019.