The answer to this question is obvious. There’s been a deluge of evidence showing the systemic inequalities in the Peoria area.

In 2015, Peoria was ranked the 6th worst city in the U.S. for black people by 24/7 Wall St.

“The poverty rate of 28.2% among the city’s black population is well above the poverty rate among the city’s white residents of 10.4%. Similarly, the median annual income of $58,563 for white households is more than double the annual income of $28,777 for a typical black household.”

24/7 Wall Street

In 2016, Peoria was ranked the number one worst city in the U.S. for black people by 24/7 Wall Street.

“Black members of the workforce are far more likely to face difficulty in finding a job than their white counterparts. The black unemployment rate in the metro area is 15.3% compared to a 5.4% white unemployment rate. High incarceration rates also play a considerable role in contributing to regional inequality. Black Peoria residents are nearly nine times more likely to be incarcerated than white residents.”

24/7 Wall Street

In 2017, Peoria was ranked the 2nd worst city in the U.S. for black people by 24/7 Wall Street.

“The typical black household in the Peoria metro area earns just 43 cents for every dollar a typical white household earns, one of the largest black-white earnings gaps of any city. Differences in income are partially responsible for the large poverty gap in Peoria. While just 8.6% of white residents live below the poverty line, 35.2% of black residents in the city do… The difference in age-adjusted mortality rates of black and white residents in Peoria is one of the largest in the country.”

24/7 Wall Street

In 2018, 24/7 Wall Street ranked Peoria as the 5th worst city for black Americans.

“Peoria, Illinois, is one of many cities on this list with a long history of segregation, the effects of which linger today. Black Peoria residents are much more likely to struggle financially and far more likely to face difficulty finding employment than white Peoria residents. The metro area’s black poverty rate is 37.0% — higher than the national black poverty rate of 26.2% and well above the metro area’s white poverty rate of 9.2%. Additionally, 17.9% of the metro area’s black labor force is out of a job compared to a white unemployment rate of just 5.6%.”

24/7 Wall Street

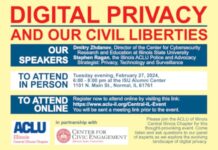

in 2018, the 17th Congressional District was listed as the 3rd worst district for black Americans by 24/7 Wall Street. The representative for the 17th district is Democrat Cheri Bustos, a centrist with a terrible record against holding President Trump accountable. She has repeatedly voted to authorize the overreaching surveillance and military powers to Trump, voted against accepting Syrian refugees, refuses to support a Medicare 4 All plan, and has done little to address racial inequalities in this country.

“Currently, the typical black household in the district has an income of just $25,840 a year, about half the income of $51,047 of the typical white household. The black unemployment rate in the district of 21.6% is also nearly four times the white unemployment rate of 6.6%.”

24/7 Wall Street

In 2019, Governing magazine named the Peoria area schools one of the most segregated in the country.

“The city of Peoria has its own school district, a chronically troubled system with a declining enrollment that serves mostly black students. About 70 percent are low-income. White families have been avoiding the troubles of the inner-city school district by moving to the northern part of town, where they can send their kids to Dunlap instead… The Peoria area, in fact, has the most segregated public schools among black and white students of any metropolitan area in the nation, according to a Governing anaylsis of federal enrollment data. The region’s schools are more divided by race than those in metropolitan Boston, Detroit or Little Rock, all of which have been major battlegrounds in fights over school integration.”

Governing

Furthermore, Governing magazine also designated Peoria one of the most segregated cities in the country.

“Through unspoken traditions and ingrained attitudes, as well as explicit government actions, city officials are in many ways responsible for maintaining a system that still divides whites and blacks. When it comes to land use — what gets built where — governments use zoning restrictions to keep out rental housing, which attracts blacks and other minorities, from predominantly white areas. They approve new residential subdivisions with strict deed restrictions that make large swaths of communities unaffordable to low-income residents and often explicitly bar any use other than single-family homes. As they restrict where apartments can be built, local governments also play a big role in deciding where public housing and other taxpayer-supported affordable housing projects are located. That often leads to concentrated areas of low-income housing in black neighborhoods. Those changes almost inevitably become permanent, because the income restrictions and other rules that come with public subsidies last for decades.”

Governing

“In Peoria, the Illinois River is a 900-foot-wide chasm between poverty and prosperity. On one bank is the city of East Peoria, which is 92 percent white, with big-box retail stores including Costco, Target and a Bass Pro Shop just a stone’s throw from the river. On the west bank is the city of Peoria itself, just 57 percent white and becoming less so every year. There, the riverfront features the Taft Homes, rows of barracks built after the Korean War that are now used as public housing, despite efforts to replace them. Farther south, one ZIP code on Peoria’s southwest side — 61605 — has become local shorthand for urban blight. It’s about 58 percent black, with a poverty rate of 44 percent and an unemployment rate of about 20 percent as of a few years ago.”

According to At-Large Councilmember Dr. Rita Ali, a black man on the Southside of Peoria will live ten years less than a person that lives in the north part of the City.1

“Capitalism only can thrive if there is an amount of poverty and those at the bottom of the food chain are usually people of color,” said Pastor Marvin Hightower, President of the Peoria NAACP. And while the solution may not be pretty, ”it’s gonna take being comfortable with being uncomfortable.”2

Peoria City Council has attempted to address the issue of systemic racism. In 2017, they held a number of community meetings on race to address the issue. According to Pastor Marvin Hightower, President of the local NAACP, “The talks that were held focused on problems but didn’t really deal with the issue of racism,” he said.3 My grandmother and I attended the second community meeting held at the Peoria Civic Center. Tables were set up with each one having a city employee to facilitate conversation. They asked us to write down things we thought could help address the racial issues facing the city. I recommended an elected Police Review Board with the power and funding to investigate and punish bad PPD behavior if necessary. The City employee at our table (unbeknownst to me) was none other than Police Chief Jerry Mitchell (now retired). He pointed to my recommendation and flat out declared that would never happen. Incensed, I challenged him on why he felt the police should not be held accountable to the people. He replied that if individuals had an issue with PPD, they could direct the concern to him. He then left the table and instructed one of the cameramen to take photos of me, likely for some nefarious purpose.

In the election for At-Large city council seats this year, there were three African-Americans who made it to the general election: Dr. Rita Ali, Andre W. Allen, and Aaron Chess. Dr. Ali is also the Vice-President of Diversity at Illinois Central College, and she brought a wide range of experience in fighting for racial equity to the table. The most outspoken voice for racial equity was caucasian Peter Kobak. You’d be hard-pressed to find a single candidate forum where Kobak wasn’t forcefully demanding Peoria take personal responsibility for its legacy of racial inequality, and he came strapped with a list of policy proposals to address these important issues. Kobak’s passion for racial justice was so strong, Dr. Ali publicly gave him praise on his willingness to address these issues. One African-American candidate told me in private, that while they agreed with everything Kobak said and proposed on racial justice, they themselves felt if they came out as strongly on this issue as Kobak, they feared being labeled a radical revolutionary and risked turning off more moderate voters.

Dr. Ali was the one African-American candidate to win a seat on city council. She joins conservative financier Denise Moore (District 1) as the only two black members on Peoria City Council. Allen came in sixth behind conservative capitalist Sid Ruckriegal, losing by a mere 408 votes but cementing his political viability nonetheless. Aaron Chess came in last.

However, not everyone on city council is as convinced that systemic racism is an issue in Peoria. John “Mr. Growth™” Kelly repeatedly expressed his extreme skepticism that institutional racism was even real, often condescendingly ignoring the claims of black Peorians. Our alleged servant-leader, Zach Oyler, while more tactful than Mr. Growth™, was also doubtful about the governments ability to address racial inequalities. He stated multiple times that local government is really only for fixing infrastructure and providing Fire/Safety to the town. Of course, when we talk about institutional racism, the very institutions we are referring to are often–though not always–government entities. And city council has done little but grant lip service to addressing this issues. They held the various community forums on the issue, hired a diversity officer for the city, passed purely symbolic resolutions against Islamophobia and for a Welcoming City but resolutions functionally do little.

In Part 2, we’ll examine the Peoria police and state’s attorney’s role in contributing to systemic racism.

This article was originally published on Strangecornersofthought.com.

- https://week.com/news/digging-deeper/2019/04/11/full-video-bridging-the-gap-town-hall/?fbclid=IwAR3q7V5Nfz4w-gXPBNVXYprs5lmhOS_A7N5AwJpryriqRNCQt74JaE_0P0g

- https://week.com/news/digging-deeper/2019/04/11/solutions-how-to-bridge-the-racial-gap-in-peoria/

- https://www.pjstar.com/news/20180817/peoria-hires-assistant-city-manager-diversity-officer